Firstly: guidance if you are a legal professional engaged in litigation regarding this project. If you have found this article, others will.

Nothing made the negotiations about joining the 3rd Bosphorus Bridge

project stand-out.

Occasionally when the phone rang it was an interesting-sounding lady,

a "headhunter" in Singapore, who made further enquiries about my

readiness to go to a job to the East, entering Asia. In the general

context, it was "just another" - someone trying to string a deal

together.

In the green fields of the Peaks with family in the Christmas of

2014-2015, the phone rang again, I confirmed that yes I would still be

interested.

It was explained that they were under such pressure didn't have time

to conduct interviews etc, and they knew I had the right

abilities (!), so they were going to proceed immediately. Yeah,

right...

Then "wham" - through came a Contract.

This was for real, and the time for it was now!

The details were I would be going to Turkey, to work for a Korean

organisation headed by Hyundai.

The job would be based around Istanbul.

Searching the Web, for the first time I found there was an industrial zone in Turkey around Sea of Marmara.

I was later to have it explained - the tectonic plate "fault" which

causes earthquakes which occasionally erase entire towns also gives

Turkey the Sea of Marmara. Which I was to realise is an enormous

commercial advantage around whose Eastern extent is a huge industrial

zone.

Any ship can get in and out, yet the place is sheltered and transport

is easy and cheap.

[The Sea of Marmara is almost an inland sea isolated from all others

by two long narrow channels, the Dardanelles to the South and the

Bosphorus to the North]

In all the world Hyundai chose to come to me. Why would they make that

selection amongst all the people in the world? There was nearly

US$1Billion "on the line" and they decided I was their person to

navigate them out of trouble.

I am a welding engineer who can actually weld. That is one appeal.

I combine science as a metallurgist having done extensive study of

welds with engineering as I transitioned to being a welding engineer.

That transition from scientist to engineer made possible in my case by

having worked for some time as a Tradesperson welder.

Therefore, I can apply my scientific and engineering knowledge in the

context of a deep insight into welding. The nature in which a weld

"controls" is probably impossible to capture in a text description.

Yet a scientist working as a welder can see and identify many

fundamental physical principles of the Universe in action governing

what they are doing and manipulating.

The employing company made contact. They became represented by a voice - a charming-sounding lady handling Visa and travel matters. Whose family-name, as seen in emails, presented a mystery where you could not start to guess how it might be pronounced.

There was a desire and pressure for me to be there immediately.

I soon had to be blunt. "'Welding engineer' is a job with a lot of risks. What happens if I turn-up at a hospital with an injury obviously caused during work and I am on a tourist visa???".

The Turkish Consulate in London gave what I suspected (correctly) was

a microcosm of the country I would be going to live in for a while.

It was simply "different".

I managed through a bit of organising with a British company to get myself a "Maintenance and Installation Visa" to go out to Turkey "to install and some equipment supplied by this Company".

What I'm finding-out about the area I am going to is too tentative to mention here.

The Turkish language. As they use the Roman alphabet (what we use

across Western Europe), it seems that should give you an immediate

head-start.

So off to the book-store I went, emerging with "Complete Turkish" by

Pollard and Pollard (he's native-English; she's native Turkish). I'd

recommend it.

Trying to explain forward from what little I had heard about Turkey cannot work, as almost nothing was anything like right.

Turkey as much as I came to understand it is best explained retrospectively from what you find being there. So here is the preview I chose to offer:

* the Turkish language is much better scripted by the modified Roman

alphabet. No other reason - solely to serve their own interests.

Turkish was clumsily scripted by Middle Eastern scripts, causing

historic literacy rates to be low. In forming modern Turkey, they did

something about it. Full success. Turks you meet who speak English

know how to slow-down and enunciate their language in a way which is

easy for "us" to understand - but that's deluding. Turkish is a

full-on Middle-Eastern language (?) and it "hits you full-on" when you

have to speak with people who speak only Turkish.

Specifically to knock-down a common "Western" misapprehension about

why the Turks switched to the Roman alphabet - it was 100% about their

own indigenous "thing".

* Where I've mentioned Turkish names, I've not used the Turkish-modified letters where they arise - I've defaulted to the "original" Roman character (pronouncing Turkish sounds requires re-training how you produce sounds to include completely new sounds - better not go there in this mainly engineering story)

* Turkey as I met it was dominated by the image of

Mustafa Kemal Ataturk

[External link]

[if this link doesn't work, it might be because there is one of those

special Turkish alphabet characters in his name]

who was at the centre of forming modern Turkey in the 1920's.

That is almost a spiritual guidance - "What would Ataturk want done?".

Much becomes understandable then.

A rapid whirl of activity had me ready to go, I packed what I best guessed I would need, and headed-off. I was now being funded by the Company, so I was able to do things for instant speed.

First slight consternation was seeing a whited-out landscape flying

over Eastern Europe. Seeing sleet (heavy wet snow) falling around the

plane as it manoeuvred in to the terminal at the airport caused not the

greatest emotion, as I'd filled my suitcase with short-sleeved shirts.

There's a world of difference between Istanbul, which I was to find

has a full four seasons, and Antalya down on the Southern,

Mediterranean, coast, where Brits going on holiday.

A quick mobile phone call has the next adjustment I need to make - the chauffeur-driven limousine. Sloshing through the slush, we are soon heading North up the hilly forested country by the Bosphorus. Arriving at the "main project compound" at the Bridge.

As the limo. sweeps along, I'm overcome with a sense "What am I doing here?! Surely they can't have got this right, that I am the person they need? They will find out - might as well enjoy what I can and accept being firmly put on a plane home when it happens". Life has taught me to "play the game", "act-out the part" and see what happens - because you never know what the twists-and-turns might bring.

The chauffeur exchanged a few words with the security-official on the gate, the barrier swung open and I was in the compound. I stepped-out into...

A freezing white-out, surrounded by the howling sounds of the frozen hard wind from the North. The 300m-tall concrete towers of the Bridge evoked awe, then standing "alone", looming over the site. So you had to tip your head well back to see the top, coming in-and-out of view in the low snow-laden cloud scudding by, sometimes making even the aircraft-warning red lights disappear from view. The Black Sea contrasted the whiteness, being solid black - very apply named. Ships slunk off to the horizon, to which I could little help attach a false foreboding of never being seen again as they disappeared into the snow.

Lead into the project office, I was introduced to the bright young lady whose voice I'd heard. I had at least got some approximate idea how to pronounce her family name by then (but which I never attempted to inflict upon her). Fortunately she had a very jolly simple-to-pronounce given name which suited her perfectly.

The snow had turned to proper crisp snowflakes and roads were closing, so she'd organised a room for me in the compound, I was assured. Leaving me untroubled and feeling well-taken-care-of as I started meeting the Korean senior Hyundai personnel I would be reporting to.

The names in emails became real people. I'd already been sent some specific information, so I could infer the approaches they were using, from the steels, welding techniques and exact details thereof, etc.

The most senior person I was ultimately responsible to, the Head of the quality organisation (in effect everything to do with manufacturing the bridge) made a personable greeting and had me sat relaxed by his desk.

He commented that the task I had described was not the current top priority and here was their current topmost issue. Spreading drawings across his desk (I won't go into details, but it can be known in this narrative by reference to "Kocaeli", the place (the "c" has a pure "j" sound in English phonetics - the rest match English phonetics)).

Result - within two hours of arriving, I am locked-onto task and never stopped working 'til I left four months later.

I had to do one of the fastest adjustments I'd ever done - in all the world they had found the right person...

Whatever the twists-and-turns life had brought me before; the only reality which mattered now was all their problems were within my comprehension and I could see the type of strategies they would need to use to get out of the problems shown to me.

Walking out for "fresh air" (very fresh - swirling snowflakes blew onto your nostrils with that particularly vivid sensation), the only vehicles moving were minibuses with snow-chains fitted. So much for my short-sleeved shirts :-(

My room in a portable cabin was warm and "en-suite". Functional and I slept well.

The catering block had a huge hall serving Korean food. The

television screens on the walls showed Korean channels. Tired Koreans

gained sustenance from their familiar Korean food.

I joined the line at the counter, copied others as best I could in

stacking my plate, took my chop-sticks and got on with it.

Result - in those first few days in Turkey, at "the Bridge compound" I

never tasted any Turkish food. In entirety it was a Korean immersion.

As the snow first lifted, I did get a ride with the minibus to the

nearest metro terminus, getting out at the nearest town of Sariyer.

Getting clear indication from the driver of where-and-when to

flag-down the bus on its return journey.

It was initially a "freaky" experience. It did all look and feel

incredibly "different". I was later to find that a lot of European

Turkey is a lot more cramped and therefore intense on the emotions

than Asian Turkey. A coffee in a nice cafe on a pier was pleasant and

made me feel at-ease.

My story was to be centred on Tuzla, the Eastern edge of Istanbul - Asian Istanbul.

As the snowstorm lifted and the roads re-opened, the original plan was

resumed, and the charming "Visas" lady got a chauffeured limo. and

accompanied us to the far Eastern edge of Anatolian Istanbul, where I

was to be based near the shipyard subcontractors.

That's at least a two-hour journey, with the Istanbul traffic (hope

"my" bridge helps now - alongside all the other infrastructure work).

A quick stop for a coffee and first immersion in Turkey put me further

at-ease. I was sure I would like it here.

My in-UK inspection of on-line map programs had been somewhat right, and the vista of a seascape lined with a vastness of shipyards came into view as we crested a final hill heading around to the Eastern edge of Istanbul.

We stopped-off first for sustenance at a restaurant I was later to frequent often, and was guided in having a feast of proverbial proportions. To become familiar - the Turkish style.

Then up into the Tuzla project-office which was to become my work "home". Introduced and desk assigned, the rest was for me to improvise - as generally comes to me and others in my situation.

I'd been booked into a holiday hotel in the local resort on the other side of the peninsula - largely empty and glad of the custom in the off-season. I was dropped-off every afternoon, and collected outside the hotel in the morning, by one of the Koreans from the office.

I was soon wandering out into the nearby resort-town area, getting my evening meals and feeling very happy.

My Turkish so far got its first application, helping me to get an insight into the familiar. A small child, in their "terrible twos", was being lead along exclaiming "No! No! No!", refusing to co-operate in heading home. Similarities tend to exceed differences ! :-)

So life was comfortable and I was able to concentrate. An enduring feature of this assignment...

The first month was to be dominated by "Kocaeli" matters.

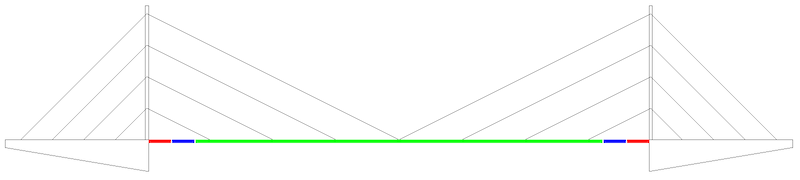

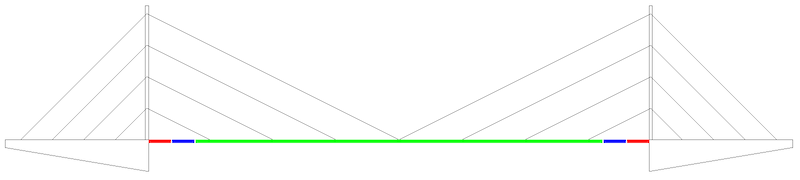

However, the bridge-deck (1.4km span and 59.4m wide - no wonder it presented issues) came to me immediately when I was bid accompany the Tuzla boss on a walk-around. The shipyard was massive, and the small part of it set-aside exclusively for the bridge-deck contract was in itself a huge enterprise.

Stated without explanation. The "Neta" factory a few km away

stockyarded the steel plates (several tens of thousands of tonnes -

high-performance - not "commodity" grades) and mass-produced

repetitive sub-assemblies small enough to transport by lorry (it was

the one site without sea access). The Tuzla shipyard assembled

stiffened-panels as accurately as could be done on a panels

production-line, to maximally simplify later assembly activities. The

Tuzla facility was a "factory" environment. Those panels were stacked

on a small ship which took them across the Sea to the Altinova

"assembly yard" - which I was not to see for more than a month, given

the priority of the "Kocaeli" work. The "assembly yard" was very much

"a construction-site" environment - as had been described to me. The

end of the story, not yet in view to me, is that the bridge-deck

sections, 24m long and weighing 760 tonnes, already painted in huge

sealed and environmental-controlled grit-blasting and spray-painting

halls, were transported by a specialist ship across the Sea of

Marmara, past Istanbul and up the Bosphorus to the bridge site, where

the deck-sections were lifted directly from the ship to its position

adding to the installed bridge-deck.

The presence of the Sea of Marmara changed everything, in terms of

economy and the chosen solution.

Little note - driving a several-hundred tonne item off the quay and

onto a ship is made to look that simple. By computer-control on the

transporter and the ship - which has powerful pumps throwing water

overboard from ballast-tanks in exact match to the weight landing on

the ship. Producing the illusion that keeping everything level in the

two "horizontal" dimensions and constantly at the correct height

matching the quay simply "happens".

The overall concept is that there in Turkey I was seeing a lot of

newer technologies applied for the first time.

Bit of explanation - in Britain, the "residual" practical activities

serving "the service economy" are often astonishingly "backwards". A

few years previously at a steel fabrication shop I worked in, a

Rumanian new-starter was visibly in a state of wide-eyed

thousand-yard-stare shock at the conditions we worked in, sitting in

the tea-room at our first break. He'd never seen such crude conditions

like this in his native Rumania, let-alone in Spain where he'd worked

for a few years.

I'll return to "Project meetings", to which I was first bid come to one by the "Tuzla boss", only a few days after arriving.

A summary of the state of the project as I arrived came to me vividly.

All the functions of the overall project - all the meetings with

several person delegations from each party travelling great distances

in chauffeured cars and company vehicles, all the invoked procedures,

formal requests for information and their written responses - all

following protocols triggered on that initial alert of finding quality

and schedule off-course - were passively recording an unfolding

calamity.

Passive in that, at this great expense in persons, procedures and

administration, there was zero effect of exerting any form of

"steerage" to the project.

Re-iterating harshly - the project was "burning-up the budget" to "drown in a sea of paperwork" which had zero functional relation to the bridge construction activity; which was dragging-along in some "lowest common denominator" unsteered way also burning up budget for no useful outcome.

This fate had only descended on the project as the steelwork phase started, as far as I know. The previous concrete construction phase of the bridge approach buttresses and the towers had run to-schedule and to quality goals.

My recruitment seems to have been because of a higher-level comprehension that welded steel structure needed a specialist with aptitude for it. The project needed me to be that person; to apply steerage and engage propulsion, I also appraised at this initial juncture.

The office had another welding engineer, a youngish Turkish man. A privilege to work with, whose name was Ibrahim. Though I was also to see and understand why I was there.

We were to drive to and from Kocaeli frequently, for most of a month.

On first visit, I could see what had gone wrong.

Containing the situation and getting the right components into the

bridge needed some ingenuity.

I was also very much puzzled. The component was a strut which clearly

took moments (bending forces). In cross-section a couple of metres by

a few metres, and well over ten metres in the length dimension. I

couldn't make sense of its design, as I couldn't see the purpose of

"odd" features which were causing all the weld trouble.

Big mental note to self that knowing the answer to that "mystery"

might help.

We beat a retreat back to Tuzla, had a night to sleep on it, then next morning considered the situation.

A poor weld detail had defeated all efforts to inspect it.

In a situation where we definitely needed those inspections.

All the usual "surface" inspections had been done, let that be clearly

understood. We definitely needed the specialist "volume"

inspections. Of the type for which Radiography and/or Ultrasonics are

the usual candidates.

Radiography was completely ruled-out by the geometry, enabling all attention to immediately go to the Ultrasonic Testing methods which would generally be expected for this thick steel structure.

We had to identify something which could be done.

The blessing was Ibrahim was a qualified and experienced "Level 2"

Ultrasonic Testing operative, aside from being an engineer.

The puzzle of the design of the "Kocaeli" component had me catch a

ride to the main Project office at the compound at the bridge site.

The Chief of Hyundai's on-site design team greeted me in the design

office. A very polite economically-speaking man, immaculate in formal

office attire, absolutely the image of an oriental academic and

intellectual person.

I'd already sketched an alternative design to the "Kocaeli component",

an elementary fabricated square section, with a few simple

calculations suggesting why it would do the same job. Which I

explained would be so quick and easy to make that, if it was

satisfactory, might that not be the quicker solution?

"Ahh - the problem with that design is it would be too stiff. It must

match the stiffness of the concrete it attaches to, otherwise the

concrete would locally crack at the attachment to this strut".

This explanation made instant sense - the design of the "Kocaeli

component" had that effect of much-reducing the stiffness.

The Chief Designer reached across to one of several few-inches-thick

files, found a particular page, and laid it open in front of me. I

could see these were "Second Moment of Area" calculations, about

stiffness of a beam. The several pages of mathematical statements

leading to the answer revealed the matter required detailed accurate

analysis. A more complete, succinct and helpful answer could not

possibly be formulated.

I was able to warmly thank the Chief Designer for his clear

explanation, and a relaxed atmosphere allowed me to sink back into a

couple of minutes of contemplation.

There remained irrationalities in the details of "the Kocaeli

component" which could be avoided on a remanufacture. However...

The component required very accurate compatibility-matching. This

additional engineering-design requirement deliberately limiting

stiffness below a specific value made a very quick replacement much

less feasible. Both in terms of needing a careful

extensively-reviewed design, and in steel fabrication and welding a

complicated form demandingly machine-accurate fit-up and a lot of

welding. My experience of chopping-up steel and welding told me

replacement would take time.

I described my thoughts to the Chief Designer, about the extensive

hard work to "us" in enabling acceptance of the current "Kocaeli

component", how the "stiffness control" issue prevented a very quick

replacement, yet if "the Kocaeli component" were found to have any

serious defects in the course of our "acceptance" inspection it could

not be feasibly repaired and would need a remanufacture anyway.

That, on balance, it seemed best to try to "accept" "the Kocaeli

component", while developing preliminary thoughts about how to

remanufacture.

He expressed that he had no problems with this view.

Back to Tuzla...

The proposal currently presented for the ultrasonic inspection we were

soon to dismiss. We could see it couldn't work, and challenged the

subcontractor to

produce a test-block with a machined-in pseudo-defect and show us they

could see it

.

The test we proposed was clearly reasonable and everyone wanted that

answer. The Ultrasonic Testing contractor could not image this huge

"perfect" pseudo-defect. Done - move-on.

I'd seen the Client's representative in meetings, but this was the

first time we'd "rubbed-shoulders" on-site. Good closer "intro".

He's the person having to control and justify where almost a billion

US-dollars is going.

The developing idea discussing between myself and Ibrahim in the Tuzla

office was far too novel and without precedent to offer it up for

discussion. We needed to "pilot" it - test the key concepts ourselves

- for feasibility, then reveal our idea(s) if the trial seemed

promising.

Without explanation - the idea was a transmitted-beam approach [

transmitted-beam UT technique explained]

Therefore; Ibrahim lead on the details of what we would need, then he

phoned the "Kocaeli" subcontractor and stated that list. There was no

Contractual clause mandating that, but equally, we knew anything which

broke the impasse was to their advantage, so they'd cooperate. We'd

already seen they had a good Ultrasonic Testing set, of a type

Ibrahim was familiar with. We turned-up and what we'd asked for was

in a stowage-crate. The Ultrasonic Testing contractor had understood

what the idea was, and one of my early Turkish surprises - they'd

added pieces of improvised equipment I'd never heard of existing for

that approach. Respect would be called-for in rather large quantities

for abilities present in that indigenous industrial region.

The box in the office and the absence of people around was expected - everyone - the subcontractor, their UT subcontractor and the inspection agencies - was keeping clear and avoiding being seen to be associated.

We rigged-up the kit and soon had the transmitted-beam angling down at a shallow angle through the plate steel, bouncing off the back-wall and coming back up to be received by the other probe some distance along the plate. As we hoped would happen. We'd got that far. The technique for the welded joint needed the weld-cap ground off flush with the plate, and I picked-up a nearby 9-inch angle-grinder and got that done over a couple of hundred millimetres of the joint.

The distant group of people were coming ever-closer, and by the time we were probing the joint-area they were right up beside us. Then helpful suggestions started. Before long everyone was in discussion.

It became clear why the technique is "never" used - it is a miserable fall-back - incredibly slow and hard-work, vague and offering no great accuracy [ explanation ]. It fulfilled the engineering need. However, these realities revealing themselves to us detracted from the sense of jubilation we might have felt.

With the technique "piloted" and being seen to work, and no other technique being available, everyone got behind this one demonstrated technique, about which it seemed obvious there would be no competing alternative.

That finished the "Kocaeli" work for me, leaving me free to transfer my attention to the bridge-deck, which desperately needed this attention.

The designer of this component came from a trading area, a place where

companies interact in a locally developed norm, in a different

geographical area. He seems to have been unaware of the implicit

assumptions which made his designs work in that trading area. One

infers that the steels traded in that local market were high above

"commodity" grade. There must have been some preferential trading

arrangement, with the steelworks supplying steel at well-above the

globally-traded "commodity grade" steels minimally meeting well-known

Standards.

Making-up the payload limit of a truck already traveling the short

distance from steelworks to customer would eliminate most

price-differential between the local "excellent" and global

"commodity" plate.

There are reasons why this is systematically likely in a trading area

with excellence. Companies with excellence will produce

high-performing products by specifying materials and components of a

high standard. Taking the example of a steelworks; set-up with

processes inherently meeting the highest standards for which there is

a market, those processes can't be "turned-off" for apparently

"commodity" grades. Which will have a lot of the qualities of the

highest-specified steels. Local companies will habituate to the

quality of the steel and make little economies here-and-there in what

they do making products, knowing their steel can "take it".

Every aspect of the design of "the Kocaeli component" hinted at some

other world found elsewhere where things did work in the way intended.

In support of this surmise, I do know that the subcontracting

arrangement - the accepted bid and the chain of actions embarked-upon,

had just one designer engaged. With all good intentions. But without

cross-checking and an environment of various people contributing,

likely interjecting in the design process, the outcome was

systematically wrong.

General point: "preferential trading arrangements" is why you cannot uncritically accept the argument "But these Specifications have worked perfectly well across many previous projects!". The argument that it worked before, so it must work now. You can find that the Specifications only worked because of local preferential trading arrangements which would not exist when operating elsewhere. Requiring an engineer to reject the apparently irrefutable "worked well previously" contention.

There is a contradiction in wider intentions here. A "preferential

trading arrangement" does keep prices down and create "our local

thing" which keeps-out competition. As the way the design works is a

local secret. Yet Standards aim to produce generality and make

everything a traded commodity, driving down prices. However,

ultimately, "commoditisation" must remain incomplete, as communication

and interaction up-and-down a trading network will optimise what

emerges at the end of a manufacturing process. Which will typically

manifest as "a good reputation" - pay for the reputable product which

performs in a superior way faultlessly, to maximise your revenue with

all effort going to optimising your own trading activity.

The contradiction between differentiation on excellence and

commoditisation for lowest price will always exist.

"The Kocaeli component" was, in a way, an annoying digression for us, a diversion of effort from where we needed to be directing it. We were doing work already paid-for. Yet the schedule implications left us no choice but for everyone to jump-in and sort it out.

Something I'd come to appreciate was Turkish hospitality. Most worksites have a waiter personing a drinks kitchen, providing teas and coffee. Once I'd arrived to have a meeting which must become a "bust-up" with the subcontractor company. Yet the waiter, seeing me arriving in the Hyundai car and running to get changed into work-clothes before following the others into the factory, had made a Turkish coffee and stepped-out presenting it to me as I charged along the corridor. Swigged-down in one but massively appreciated.

The Managing Director, a wizened industrial character who spoke only Turkish, often gestured for me to go into his office and use the large leather swivel-chair to recline and rest.

Despite confrontations, I tried to be helpful where I could. In one case I could not believe how badly an intention had been implemented - extracting samples of steel from the welded structure to test if the steel is exactly the specification and batch it is claimed to be. I could see a way which would be non-destructive. To the Client's representative I described the much better way he could obtain a sample. Without explanation - take the trepanned "discard" from a mag-base drill as your sample to analyse. At the subcontractor's, the Managing Director lead me into the Accountant's office, who did a sentence-by-sentence translation of my explanation given in English accompanying my sketches. The company got the equipment from amongst what they already had and suggested it be used to the Client's representative. He'd have known my "hidden hand" in this, but all was improved and good-will was added-to.

A note about what I was seeing of Turkey...

The journey from Tuzla past Kocaeli and Izmit was 100km "solid" of

industry. It was like the British Midlands of my childhood into

youth. Steelworks, concrete-factories, huge "portal-frame" workshop

buildings of inscrutable purpose, huge expanses of oil-refinery around

Izmit, smoke and steam, lorries and railway trains everywhere. All I

remembered of my childhood had reappeared here. Dusty and somewhat

polluted, but bringing an earning-power which drew in vast numbers of

people to work there.

I was indeed wistful as we smoothly cruised back-and-forth in our car

- bearing a Western-European badge but which I knew to be made in

Bursa, just to the South in Turkey.

The hospitality and quality of the food I was meeting in these heavily industrial areas was such that I was realising that the stories of excellent holidays in "beautiful" tourist areas of Turkey were one-and-the-same as what I was experiencing. The inherent nature of Turkey and the Turkish people.

At the outset, Hyundai's main intention as I was being recruited was

that I would sort-out the bridge-deck manufacturing issues for the 3rd

Bosphorus Bridge project.

"The Kocaeli component" diverted a lot of my effort in the first

month.

However, I'd already been to meetings about the bridge-deck, and it

was instantly clear both that they had got in an enormous mess over

several issues and that each one of these was within an area of

knowledge and experience I had. Fortunate for me. Hyundai had

recruited the right person; that was definitely a fact.

On the other hand, the manufacture of the bridge-deck was all-but

stalled. Which was extremely bad, with huge financial consequence.

Irrespective of the trivial stupidity which was the root cause of most

problems.

Now freed-up, I headed to the Altinova assembly-yard. Completing my

picture of the state of the project. The Altinova assembly-yard was

an impressive operation, organised using large-project-planning

abilities which can only be mine in the future. However,

equally-much, I could see there were serious absences of sound

leadership regarding welds which were creating a lot of problems at

the assembly-yard stage too.

The much greater amount of good was being completely overshadowed by

the small amount of bad coming from weld issues. Hyundai had

instinctively and intuitively comprehended this, even though they did

not have the answers themselves prior to recruiting me.

The problems had revealed themselves to me in sufficient detail, at a

time it was clear that the parties were rapidly heading for

litigation.

This needed "heading-off" and prevented from happening, otherwise we

would all be losing our jobs.

A step in the right direction, brought about in a way involving some cooperation, was needed to pull back from that disastrous evolution.

I could see immediate steps which would get some quick improvements.

The problem was the politics of getting will behind the right actions.

Only interaction with the Client's representative could do it. A delicate political act in the circumstances. On the other hand, I had been recruited by Hyundai specifically to sort-out the situation...

Going into the office of the Client was an issue in itself. All

"external organisation" offices at the bridge-deck subcontractor's

yard were in the same area of the shipyard. Inspection agencies, the

lead contractor (my employer) and the Client's representatives office.

So I should assume everything would be seen. Especially in this

acrimonious political atmosphere.

The way was to manage it - a private conversation seen by any observer

to be "proper".

Going into the office of the Representative of the Client for the

first time, and saying I wanted to have a chat with him, as he reached

for his notebook I stated "No - no notes. And we do not stay in here.

We go outside and walk around". That stated by me inflexibly to the

most powerful person on the project. Comprehended, we pulled-on our

hard-hats and we walked out. The general idea was; nothing about our

persons, hands in view doing nothing, clearly making no notes or other

record, having a conversation known only to us.

We strolled down the ship-repair part of the yard, away from unwelcome

attention and with the massive activity of fast turn-around ship

maintenance providing a background noise giving us perfect privacy to

chat.

Avoiding hazards and navigating around the areas of intense local

activity provided a "diluting" backdrop as we strolled along, in

unhurried contemplative chat.

It was one of those conversations of careful questions, serving to

identify and acknowledge our shared interests. Not stating anything

directly, but having a shared understanding of where valuable first

improvements might be attainable immediately.

The clear purpose though: I'm hinting there will be from me a proposed

course-of-action working on the areas we are talking-around. When you

hear it and recognise it, at a minimum don't oppose it, and limit your

own teams' objections to it.

I did, of course, brief my boss that I had had the talk with the

Client's representative - so he could deal with anyone coming to him

with the "secret" that I had been seen with that person.

Anyway, in the days after that talk we did manage to get some small

but pleasing changes in the fortunes of the project, gaining pace in

time, and the vision of "being shipwrecked on the reefs of litigation"

disappeared.

My duties, working for Hyundai, the lead contractor, was to represent their interests, benefit Hyundai, and prevent other parties benefiting at Hyundai's expense.

In my earliest project meetings, it was clearly right now my duty to "go into action" disputing claims being made by parties representing the Client. Which I "got on with" immediately and forceful. In effect my job was to "trash" the various agencies (claiming to - a vital distinction!) represent the Client's interests.

Come a project meeting at the main project compound at the bridge site, the Client's Representative specifically asked Hyundai for my presence at that meeting.

How so, if I'm "beating-up" people he's paying for the services of?

I mustn't presume to speak for him. He clearly saw it in his overall interests for me to be there. I suggest he saw I was "letting light into the situation" and pointing to the way ahead.

The character of the disputing, so far as I saw it on my arrival, had been point-by-point, arguing over the exact meaning and obligations arising from Specifications and phrases in applicable Standards - an activity without "navigation" and overall purpose.

There were incredibly experienced people present representing various parties at those meetings, who I looked up to with great respect. Whose few words transcended the "noise" and lead to the important truly interactive discussions. More on that later...

It cannot have done any harm for it to be seen by the Client that the lead contractor, my employer Hyundai, had taken a "wild" determined act bringing me into the project, within their polite circumspect Korean organisation. My own mind's eye vision of situations like this is "setting a ferret loose down the rabbit-hole" ;-)

The Client's Representative's requesting of my presence was unilateral. Equally it was an acknowledgment and interaction.

As a reminder; we are considering the manufacture of the bridge-deck, which was subcontracted to local shipyards company.

As I got further into the project, these themes I immediately identified continued to be proven correct.

The "topmost" common source of two of these "themes" was the chosen

"Application Standard" to which the bridge was built: EN1090 of 2008.

More specifically: EN1090-1:2009+A1:2011 (an overarching quite compact

quality-system requirement) and EN1090-2:2008+A1:2011 (the extensive

specific technical requirements for steel structures).

(there are Standards for testing methods, Standards for how industrial

processes are done, Standards for properties of a material gaining a

certain classification, etc - whereas an "Application Standard"

brings-together for a specific application all the unique requirements

and as much as possible delegated to "normative Standards" of the

previously-mentioned type)

Compared to well-respected steel-structure Standards

(ISO's, etc) and Codes (the North American "American Society of

..." documents), EN1090 seems clumsy and insufficiently

peer-reviewed. Also doing something which it should never do, which

is over-rule provisions of the highly-respected extensively-developed

extremely peer-reviewed ISO Standards it refers-to.

"EN1090" is a "lightweight", whereas the "subsidiary" referenced ISO's

for weld quality, non-destructive weld inspection, etc, are

highly-regarded "heavyweights".

In summary: EN1090 for this application lacked the feeling of

"maturity" which other established families of Standards and Codes

possess.

Please be aware that these next-described actions of EN1090 are so

reprehensible that it should be understood it is painful and

distasteful to talk of them as if they should have any serious

consideration.

That version of EN1090 "invented" a "new" level of weld perfection,

"Execution Class 4" - above the inherent ISO5817 quality levels "D"

"C" and "B" which Execution Classes 1 to 3 map-onto - which they name

"B+". Whose epicentre is the "notorious" "Table 17" on numbered-page

59 of EN1090-2:2008+A1:2011.

Looking at the requirements as someone with some experience of

welding, you can infer "where their heads were at" when they were

constructing it. For instance some of it appears to relate to the

very specialist activity of end-to-end "butt-welding" of lengths of

steel plate which will form the lower flange of fabricated beams for

beam bridges at the upper limit of their feasible lengths at some tens

of metres. Very specific scenarios which should not be "let loose" as

general requirements, as that will have chaotic nonsensical

consequences.

These are very specific technical arguments.

The much bigger damage caused is - this EN1090 created a precedent and

mandate to "unilaterally pluck requirements out of thin air" by anyone

who choses to do so.

I was later to find that the entire contractual quality requirements

had been completely misunderstood by everyone. Obtained for the price

of two cups of coffee, some bottles of spring-water and a "trilece"

dessert (ie not a lot!). But sadly having to wait for that

entire work-day afternoon sat on the outdoor terrace of the

"Uzun Yayla" restaurant in Tuzla

[external link] (near the shipyards, and under "our"

office-block), reading the cover-to-cover the entire contract between

Hyundai and the shipyard subcontractor for the bridge-deck.

Even the designer of the bridge, whose statement on quality

requirements for welded steel structure was cited verbatim, did not

seem to have the concept of how his correctly-identified overall

requirement needed to be interpreted.

The problem is that, unless you are familiar with welds, you would not

identify that the "Execution Class" of the entire structure will be

different to the "Execution Class" of the welds comprising it.

Reasons include "structural redundancy"; the failure of one weld

will not endanger the entire bridge. The designer would avoid that -

and there are none on the entirety of the bridge-deck.

The Designer had correctly identified it would be a catastrophe of

massive proportions if the bridge were to collapse - "Execution Class

4" for the entire structure.

What no-one had understood is that this would be achieved by the

achievable and realistic "Execution Class 3" / "Quality Level B"

welds. The top level of excellence for general welds - stringent but

attainable.

To be frank - "Execution Class 2" / "Quality Level C" welds would

deliver "Execution Class 4" for the entire structure; however, the

fatigue-resistance of the welds for a service of high cyclic stresses

a bridge endures requires "Execution Class 3" / "Quality Level B" for

all load-bearing structure.

These are the three main themes:

Following is the story for each "theme".

For the materials science and engineering issue of "fatigue", search on "metal fatigue", eg "Wikipedia" page.

I have done research on fatigue-resistant welds, and done tens of

hours reading on the topic while sat beside clattering fatigue-testing

machines, occasionally getting up and observing the fate in time of

samples under test. Before the final huge "bang" as the sample

finally "let go" as the diminished remaining cross-sectional area

could no longer take the load. That was for steel welds - as matches

this situation.

My

research on fatigue-resistant welds

.

What metals with a good weld will withstand for a long time is

astonishing brutal.

Here's my take on what "fatigue" is, for what it's worth. The

ductility of metal "disperses" local attacks, making metals very

forgiving in structures. Every attack requires huge amounts of energy

to do damage to the structure - and the structure can still remain

serviceable and fully functioning. The contrast is ceramics, without

ductility, which readily shatter with little energy. Using metals, we

can design structures with many far-from-ideal but cheap-to-make

features, and "throw it all" to the metal to deal with it. Metal

fatigue is the one which you do not "get away with". The metal cannot

"disperse" the local attack of the cyclic ("repeat") stress.

Resulting in a local crack forming. However; the ductility and

resilience of the metal defeats a crack-rip, and a high cyclic stress

is restrained-down to producing a tiny crack-growth extension per

stress cycle - down at atomic distances. So you can "engineer"

serviceability by knowing fatigue cracks will occur and looking out

for them. Ready to "catch" them and use your general fabrication

techniques you used to build the structure to cut-out the damaged area

and replace it.

So, back to the "bridge" story...

The sole protagonist driving this matter was the engineering

consultancy hired by the Client to independently review the bridge

design. This was about the stiffened panels as manufactured on the

Tuzla stiffened-panel line - a "factory" environment (as previously

mentioned). A search on "Orthotropic Deck" will fully indicate

the activity - see eg

"Wikipedia"

page.

They insisted that the long longitudinal welds joining the stiffening

channels, the approximately "U" shape, to the deck-plates, had

features which were vulnerabilities to fatigue.

The mainly American engineering research on the fatigue-limited

service life of "Orthotropic Bridge Decks", cited by them as providing

the "damning" diagnosis, did not match "our" situation on the 3rd

Bosphorus Bridge project. They attached a name loaded with negative

connotations given to recurrent significant flaws in the American weld

to dissimilar features of "our" panel-line welds. Without

explanation: the Americans used "unprepped" "U"-channels sub-arc'ed to

the deck-plates at high currents giving full-penetration - such that

if conditions "loosened" from tight fit-up, if would produce a local

fairly explosive "melt-through" (more accurately, "blow-through") -

whereas the "Tuzla" practice was bevelling the edges of the "U"s and

using FCAW in a weld which varied from 95%-plus penetration to

full-penetrated with a nice smooth small penetration-bead.

Note, for what it's worth, that the majority service stresses are

along the length of the weld (?).

The Client's consultants were claiming the local areas of transition

from very-high but partial penetration to full penetration were

fatigue-stress concentrators.

All my own impressions of fatigue applied to this matter manifested as

single exclaimed dismissive expletive. Obviously only in my own mind,

apart from in private conversations in a closed room with people I

trusted.

The pressing urgency of the matter was that this engineering

consultancy was threatening to "stop the job" if these "features" were

not eliminated immediately.

The welding process and welding approach did not provide a simple way

to make that happen - as expedience would have had us do if that was

readily achievable, even if we knew the change to be pointless.

As common in projects, an inspection and consultancy agency generally

requires and obtains the power on proclaiming dissatisfaction to

prohibit further work.

My mental image was of the people in that agency being "en-masse"

engaged in a simultaneous synchronised gratuitous act of physical

self-pleasure.

How the story proceeded can be dealt with by relating the next step. The Client's Representative, needing to get to the root of this, engaged an independent Consultant of International repute on fatigue matters.

In all of Hyundai's project organisation of hundreds of experts, it

emerged that I was the one who needed to "step-up" and lead for

Hyundai on this.

It needed to be clear that Hyundai was strongly-defended, so that

trying to throw blame and costs on Hyundai lacked appeal.

Tee-hee - I'd for sure like to do a good job - but it's not my money

on the line. "Showtime" !

The parties are gathering, hosted in the large elegant conference-room

at the shipyard of the bridge-deck subcontractor.

The Consultant engaged by the Client's Representative was introduced

by the Client's Representative.

Time to get in there and get control. Be first and shape the

discussion.

Fortunately I could see how to do this with charm - much more

desirable where possible.

"Excuse me - could you help me with a misunderstanding? I have been

unable to understand how these features are the most important,

given fatigue finds your structure's worst feature, and there appear

to be far worse fatigue details which are part of the design less than

half a metre away?"

The Consultant, for whom I had massive respect and whose accumulated

experience was vastly above mine, pulled an expression conveying that

this question posed a huge complex genuine issue to address, while

making a swirling-and-diving hand-gesture to reinforce that same

message.

Straight-off down the first-principles technical direction of looking

at fatigue-ratings of design features, and the stresses in each area

attacking those features.

The discussion rapidly spread-out to rate all features of the

bridge-deck as designed and implemented - a comprehensive engineering

view - excellent!

The necessary design detail and fatigue-resistance analysis rightfully

required diagrams and illustrations, so the Consultant and I were

shortly stood beside the whiteboard with pens of many colours denoting

shapes, stresses and their flow, flaws and

stress-concentrators, etc. Soon to be joined by others who

genuinely possessed engineering thinking, in a joint activity of

sketching, "arrowing" and "ringing" as we agreed on the crucial

issues.

Perfect success, as all the parties ready to interject with

"legalistic" contentions-without-context where isolated-out, never to

get their chance.

The Client was charmed by the interactive analysis of the bridge deck

features on their merits, and condoned the prioritisations and

solutions which emerged.

The design review consultancy continued in ensuing time to try to use their "stop the job" power as a threat to force this matter back to sole-and-central consideration.

A bit more effort required from me on this matter...

I confess I wish I could have taken my fatigue-resistant welds investigative research further, and this looked like a blessing to me - if not to anyone else (!).

The Client, in a reaction to their own design-oversight consultants,

had contracted with an external testing organisation a full-sized

fatigue test on a panel.

This would be completely useless for "our" purposes in making a good

bridge.

Given the financial issues at stake, for Hyundai as lead contractor and "our" subcontractors to unilaterally and independently obtain pertinent fatigue-test results at our own expense was a "no-brainer" (an outcome so advantageous overall that it needed no extensive consideration to opt for it).

I saw two "lines of attack" on the issue. One was to isolate solely the feature of a change from high-partial-penetration to full-penetration on the stiffener-rib to deck-plate welds.

The other was - could we test entire panels? Many metres in each

dimension. Normally a fatigue-testing machine dwarfs in size the

sample it tests - but could we weld with short cross-struts two panels

face-to-face and insert some elementary mechanism into that gap which

flexed them through some fixed displacement - say for example 50mm?

That one would fail first is irrelevant - we are searching for the

worst features, remember...

There would be a squillion angry objections critiquing the method -

but the findings could not be ignored - especially as we accumulated

repeat tests.

In a shipyard, there's enough space to put the test in a distant empty

shed, stand-back and set the test going, lock the door and come back

when there's the loud "bang".

While the shipyard subcontractor for the bridge-deck did say in

principle they could contribute their resources and facilities to a

suitable test-programme, that one never went any further - because the

other action we took removed the necessity.

The test-approach isolating solely the change-in-weld-penetration

region of the stiffener-to-deckplate would fall within the

force-applying ability of a large fatigue-testing machine.

We'd have to cut-up one good panel with an abundance of the feature to

extract our samples - but it could be easily replaced, so in the scale

of priorities, that was no problem.

I'd been told that no suitable fatigue-testing facility existed in

Turkey - but I was having instinctive doubts about that, given the

competence and ability I was encountering in Turkey.

Some Internet searching indicated an applied engineering research

group investigating fatigue-resistance of structures, at a university

in Ankara. Asking around of indigenous Turkish engineers I

encountered, comments were along the line of "He was my Professor of

my Master's Degree!" referring to the leader of the group named in my

searches. Plus more happy recollections.

Phoning him, backed by an email with attached sketches describing our

situation, got an engaged response.

The tests were possible and he could do them immediately. He could

indeed "crank-up" the force to a level producing high stresses and

rapid failures, revealing what were the vulnerabilities, and how

vulnerable they were.

The immediate result: as soon as it became obvious that I / we the

lead contractors would be coming along in about a couple of weeks with

real results and findings, suddenly there was silence on the issue.

A perfect outcome for the project.

With that outcome already achieved, the tests never went ahead.

This was to prove to be a recurrent theme. Where I use my abilities

to organise for real information to be generated resolving a matter,

the problem-claiming protagonists, realising they are outclassed and

probably talking "rubbish", promptly shut-up.

Leaving me with the emotion of regret that I have used the time of

good people who were willing to cooperate with me without anything in

return, and that interesting ready-to-go investigations which would

have added to my portfolio of expertise never happened.

The "best" "face-saving" influence the engineering-design oversight consultants managed was to get an on-site inspection team, whose normal job is investigating the condition of drains, sending a crawler-robot with a video-camera down every stiffener-rib. As a Trade team, they got on with what they were paid to do, not getting in anyone's way or forcing any disruption, happily pocketing their remuneration for their performed task. A pointless exercise but a small expense in the overall project priorities in appeasing the oversight consultants.

I was able to comment in meetings and advise my employers upon the following point almost immediately on arrival at the project; though it was to be a little while before I could forcefully act upon it.

In my earliest meetings, the talk on non-destructive examination (NDE) of welds (interchangeably called non-destructive testing, NDT), in particular the ultrasonic testing (UT), revealed a profound misunderstanding of the purpose of the non-destructive testing. A commonly-encountered misunderstanding, but surprising for me to find on such a large prestigious project.

Non-destructive examination results can only tell you whether your

welding methods are giving you the weld quality you specify.

"Repair" of defects found on non-destructive examination cannot

restore quality which the original welding process did not

provide (!!!).

For economy of explanation; first consider how NDE and UT are correctly used.

You design a component - including specifying all materials, how it is welded, how it is inspected (NDE/UT), painted, etc. If the "run" is many easily-replicated components, on applying UT to your first "batch", if you found weld defects you would conclude that your welding process does not have the ability to meet the quality specification. So you go off and define a new method and specification for your welding. That first "batch" of components are discarded. When with re-design and testing you get components which "pass" NDE with no defects found in any of them, then you proceed with the full manufacturing run. With sample NDE / UT to ensure that quality remains what it should be by reason of the manufacturing process being invariant.

The same logic applies to a large high-value high-stakes one-off or few-manufactured components. Reluctance to conclude it is below-specification does not change that it is below specification.

Hence; as soon as I heard of the "strenuous efforts" "quickly" "getting around" the bridge-deck sections performing ultrasonic testing and "performing weld repairs as quickly as possible", I knew something was seriously wrong.

Obviously, gross defects found on NDE which would cause rapid failure of the bridge deck structure must be removed. Typically by gouging then repair-welding. There should be very few of these. They need to be "exceptional", otherwise your manufacturing process is totally unfit for purpose, as is the component you have made.

Here is the explanation why non-destructive examination, including

ultrasonic testing, cannot bestow quality not originally present.

That is in-general, and particularly so for welded structures.

Most structural failures are fatigue-cracking, many originating from

prior flaws and defects in the structure.

Non-destructive examination techniques, including ultrasonic testing,

have a "probability of detection" ("p-o-d") of defects. If you

inspect a welded joint, you will only detect some of the defects if it

possesses them.

Fatigue, the attack by high cyclic stresses, "probes" your structure

and will "find" your worst features.

Therefore if you "repair" the defects which you do find, you will

not change the performance of the structure.

Why?

Because fatigue will "find" the other defects you did not detect, and

initiate failures there.

Broadly the same argument applies to other "attacks" upon your

structure.

Therefore, there is no point in removing moderate defects detected.

Then there is the propensity of "repairs" to be less-good than the

original weld with a known modest defect, and be the initiation

site for failures, making your structure less good than it was before

"repair".

The discipline of "Engineering Critical Analysis" came into being from

evaluating exactly this dilemma. It's familiar and very important.

Clarifying something - no weld is without flaws. In rough-and-ready

terms: a flaw is something inevitable and within the design basis; a

defect is a flaw significant enough to degrade performance of your

structure (though may still be accommodated within the design basis);

while a gross defect causes risk of loss-of-use or even to the

survival of your structure.

So what is the actual purpose of non-destructive examination to a

project?

Apart from detecting gross defects which must be eliminated.

The majority purpose of non-destructive examination serves the

engineering oversight of the project, by being a quality-control

measure within the overall quality-assurance function within the

project.

If you are finding defects in welds, you must rectify and/or improve

your welding so the next components you manufacture will have the

quality you desire.

On my first project meeting hosted in the Altinova assembly-yard, the

ultrasonic testing issue went right there to the centre. One very

senior engineer of the Client organisation was there, speaking with a

tone of incredulity "Can the defect and rejection rates really be SO

high???". He went on to describe the reliability of these completely

familiar welding processes, to which everyone else experienced in big

fabrication-yard welding agreed. What different could be happening

here?!

This was about the regular scheduled ultrasonic testing of welds

reporting huge numbers of defects.

The magnitude of the matter was conveyed in charts the shipyard had

prepared, which everyone agreed realistically conveyed the reality.

This was the main cause of the recently started steel structures phase

of the project being almost fully stalled. All "condemned" welds were

being Air-Arc-Gouged out (

AAG

) [external link : The Welding Institute's "Job Knowledge" series] and

"repair-welded".

What was to be seen, walking around the assembly-yard, was a scene of

carnage. Welds were being gouged-out in every direction you looked,

and welding teams were trying to do awkward repair-welds in very

non-ideal conditions.

No-one had overall understanding of why this was happening to "us" the

entire project.

Repair-welds were also being "condemned" on ultrasonic testing, and

repeated re-welding was raising concerns about losing the dimensional

accuracy which had been worked-for so hard, with the vast jigs and the

frequent trigonometric surveying used during set-up. Welds shrink on

cooling and cause distortion, which presents enough challenges getting

accurate dimensions in the best of circumstances - whereas this was

uncontrolled and without overall plan.

We were in the middle of something both mysterious and disastrous.

We were walking around the assembly-yard, observing lots of busy teams working-away, with nothing observed revealing what was causing the problem. Everything looked "normal" in the first-making of the bridge-deck sections.

These "streamlined" shapes were complete in the cross-section at 59.5m

wide, made in 24m lengthwise sections weighing 760tonnes each.

The sections were made end-to-end for exact dimensional matching, to

make assembly into the completed bridge deck a single geometrically

convenient enormous-length girth-weld.

Thus, on the bridge-deck jigs, you were often on or within over 200m

of structure, and never less than about 100m of structure with a high

view down onto the rest of the jigs being fitted-up with the next

sections.

Inside the bridge-deck, a scaffolding which could finally be

dismantled and removed was encased within during the assembly

"tacking-up" sequence, providing tiers of lightweight metal decking

across which you had to walk stooped, often ducking very low to get

under big structural stiffening beams of the bridge-deck structure.

Lights hung at frequent intervals. The scaffold decking gave access

to all surfaces of the bridge-deck structure during its manufacture to

completion.

Within the structure, the lowest level upon the lower internal surface

of the bridge-deck offered more space to move, but involved walking

along beam-flanges (narrow-ish) and hopping from stiffener-rib to

stiffener-rib. Moving in groups, it was quite an energetic vision

seeing the line of people flowing along making the identical move at

each location - a bit like observing a millipede moving.

Work-teams were all over the internal space and external surfaces,

welding the welds which at the assembly stage in the jig had been

tack-welded, or locked into juxtaposition by long stitch-like lines of

"strongback" plates transversely welded-on bridging the welded-joint

to be made.

Given the huge length of the structure in assembly, and the

awkwardness of walking down the constricted spaces, it was often

expedient to enter it through hatches which would in the finished

bridge provide the maintenance access. The high stresses to be

experienced by the finished bridge, and the need for close dimensional

accuracy, precluded leaving access-openings later to be closed to

finish the structure as designed.

Ladders and railings - the various "secondary steelwork", could not be

included while the primary structure was being constructed. Making

climbing through the smallish access-hatches with surrounding thick

stress-diverting coaming, on steeply-sloping side surfaces, a very

athletic activity, often requiring lowering yourself off your elbows

braced on coaming for a long distance until your feet touched some

surface below.

Teamwork is everything, and I was present at the "Eureka!" moment when

we found our way into the explanation.

At the Altinova assembly-yard for a serendipitous visit, I joined-up

with a Korean Hyundai engineer I'd never previously met for a

walk-around.

Walking along the deck surface, we randomly came across an ultrasonic

testing technician who was in the moment of both looking at the

instrument's screen attentively while marking-up the location and

nature of a detected defect.

The Hyundai engineer, who it transpired was experienced with

application of ultrasonic testing, seeing something odd, swept-in

and got the ultrasonic testing technician to explain. The Hyundai

engineer had seen that the reflector (flaw? defect?) indication was

not as high on the screen as it should be to be classified as a

defect, according to the widely-used Standard applied here.

He asked for the ultrasonic testing probe, which he took from the

ultrasonic testing technician, and slid it around probing the

reflector the ultrasonic testing technician had marked-up as a

defect. After about half a minute of probing, he asked the ultrasonic

testing technician to demonstrate where he was "seeing" the

defect-sized reflector, which the Hyundai engineer could not find.

Then the magical moment which let us into the "secret" of what was

happening. The ultrasonic testing technician, squirming because he

realised he was about to become the epicentre of a storm, had to

explain that he was seeing the same as the Hyundai engineer was

seeing, but he was following an additional instruction

above-and-beyond the highly-respected Standard ISO11666

("Non-destructive testing of welds -- Ultrasonic testing -- Acceptance

levels"), about the magnitude of a returning-echo off a reflecting

flaw above which to report a defect is there.

That instruction was to declare a defect at a smaller reflectivity - a

less-high "spike" (peak) on the ultrasonic testing instrument screen -

that the ISO11666 criteria. ie a smaller flaw indication is

marked-up as a defect.

Background note : an ultrasonic testing set screen in use is full of

echoes from many sources, and it is an astonishing training that

enables an operator to filter out all but the very few which are

defect indications. Moreover, the operator gets to quite accurately

identify the type of flaw, from the "beam dynamics" - how the

reflector spike on the screen behaves as the probe is swept around so

the ultrasonic beam probes the reflector. You are typically scanning

around through the metal to about 100mm distance from the probe. Some

peaks leaping around the screen are "ghost-echoes" from the physics of

the ultrasonic beam changing mode from shear to compression waves and

back, some are off the physical shape of the structure as-designed so

are irrelevant, etc. A flaw reflection comes from a region

where there should be no reflector, because that region is within the

as-designed structure - which should transmit the beam uninterrupted.

The problem is that any weld will contain flaws, and engineering

knowledge is that a small flaw is best left as-is, because to gouge it

out and repair it has its own risks. Then there is the question of

whether there really was anything there at all. So there is a need

for a pragmatic Standard for interpreting and "sentencing" ultrasonic

testing indications.

Anyway, back from this aside; we'd found the explanation and

root-cause for the chaos which had engulfed the project.

(there's also the issue of what the organisation's response is to

finding weld defects on ultrasonic testing inspection, which needed to

be wrong for the effect of wrong ultrasonic testing defect-declaration

criteria to "bite")

Summarising: there was no abundance of defects; the reporting of many defects was because the inspection agencies had "played with" the ultrasonic testing evaluation criteria and were reporting defects where there were none.

The discovery was relayed back to the entire project team.

Memories jogged, it was recalled that the lead local inspection agency engaged by the Client had talked about changing ultrasonic testing acceptance criteria when in conversations with various parties. Nothing which could even approximately be construed as providing as much as a partial mandate for anything like this which had been discovered.

That the inspection agency would do something like this raised a

fundamental issue of whether they were truly representing the

interests of their employer, the Client.

It was later to seem likely that that inspection agency was peeved at

not getting a more important role they bid for on the project, so was

trying to aggrandise itself in other ways.

Trying to get an understanding of what was happening, a single defect

reported overnight was selected for re-investigation. All engineering

parties to the project sent representatives, who gathered in the

bright cool morning air, high up in the sea-breeze felt on the top

surface of the bridge-deck section as it stood on blocks at the

assembly-yard. Engineers from the project and trusted non-destructive

experts brought along ultrasonic testing sets, and they set-about

locating then measuring the size of that indication marked as a

defect.

Various parties all got to work with their ultrasonic testing sets,

and no-one could find any defect. After about an hour of searching,

the leader of the inspection agency which had reported this defect was

summoned.

In an astonishing scene, he straightened-up and sanctimoniously stated

that "We report a defect at 32decibels below DAC".

That is mind-boggling insane.

We were clearly alongside a "full-blown" case of what I dubbed

"Execution Class 4 madness".

Here is "my" quick explanation which hopefully makes these things

self-evident.

"DAC" in this common case is the reflectivity of a 3mm hole probed

side-on - "a 3mm side-drilled-hole" ("3mm SDH") - an easily-made

consistent reflector in a sample of any material you are ultrasonic

testing. The reference reflectivity, given the decibels on a

ultrasonic testing set screen can only ever be relative.

For indications away from the immediate vicinity of the probe - where

the majority of the scanning is done - the ISO11666 threshold level at

which a flaw is classified as a defect is 14decibels below 3mm SDH

DAC.

32dB below 3mm-SDH-DAC in relation to 14dB below 3mm-SDH-DAC is an

18dB reduction.

An inherent property of the decibel scale is that it is logarithmic.

Any 18dB reduction means a reduction to nearly 1/8th of the previous

reflected ultrasonic-beam amplitude (it is 1/7.94).

Getting more advanced into physics, but vitally important: the

ultrasonic vibration beam obeys wave behaviour, including not being

able to image anything smaller than its wavelength. That wavelength

for a 4MHz shear-wave probe on steel is 0.8mm. Only part of the

defect might be reflecting back to the probe - not its full size. The

"wavelength" physical limit was probably already acting.

Etc.

This is is all so crazy "you cannot go there" (it's too illogical to

be amenable to logical analysis).

What you will "see" could only be known to an omnipotent Creator - if

they would spare any time for this idiotic situation, where the proper

answer is do as you were told to - follow the Standard.

The inspection agencies where clearly "plucking requirements out of

thin air", and seemed to be competing with each other to be most

"important" by reason of inventing the most "stringent" criteria.

Having broken-free of engineering oversight, on first unilaterally

changing an ultrasonic testing defect-classification threshold some

time ago and "getting away with it".

More exposition would only be "strokes of the same brush". We had now identified "the big picture". Only details followed.

Again I found myself representing Hyundai in project meetings, this time on the ultrasonic testing matters. In the "fatigue-resistant weld-design" issue, the requirement upon me had been dominating with technical excellence. In this case of the ultrasonic testing issues, the requirement upon me was to know how to act upon the parties involved - a more "social engineering" task.

Without a "script" saying what to do in this situation, I found my intuition being the driving force for Hyundai.

Giving full credit particularly to my Tuzla Hyundai office colleague Ibrahim, who was beside me, had experience of ultrasonic testing (as I described previously) and advised me of details of Standards.

The inspection agencies initially tried to "hide" by talking in Turkish between each other extensively, claiming the matters were so complex that they had to be granted that indulgence.

By that stage my Turkish was good enough that I could recognise

numbers - for example "-14" and anything else which was not "-14".

Also what Standards were being discussed eg ISO11666,

ISO5817, etc.

If they tried to discuss between each other deviation from Standards,

I could identify that.

Therefore I had only to lean over to Ibrahim to ask him for a summary

of what they were discussing. The brief explanation providing me with

the confidence to intervene.

My clearly barked-out responses in well-pronounced Turkish of "No!"

and "False!" rather abruptly halted these "private" conversations.

(both "no" and "false" involve special Turkish sounds which have to be

scripted by Turkish-specific modifications to the Roman alphabet, and

to "hit" those sounds right in a clearly-enunciated interjections did

assert my presence there)

I could see one "place" I could act which would "demolish" the

inspection agencies in project meetings.

However, it required presenting a challenge designed to personally

discredit individuals representing other parties present in project

meetings.

Not something to be done unilaterally. I discussed with the senior

managers on-site of my employer, Hyundai. Who were Orientals inclined

to be inscrutable and polite. They solemnly concurred that my view

was also Hyundai's formal view.

The context is this: even if you were to as much as propose a

deviation from the ultrasonic testing Standards, you would have to

provide both a clear justification which stands-up to peer review,

plus a portfolio of trial results indicating that the proposed

ultrasonic testing technique delivers the claimed outcome.

This is about entitlement to as much as suggest deviation from

Standards!

None of the protagonists had done any ultrasonic technique tests,

despite unilaterally deviating from Standards...

The nature of the tests which would be required was obvious to any

scientist.

When investigating what ultrasonic testing techniques will really do,

the tests use pseudo-defects of known shape and dimensions, in blocks

of representative material.

This creates the inverse of the inspection case, where an ultrasonic

beam of known characteristics and responses interacts with unknown

flaws. In the tests, the pseudo-defects are known and the properties

of the ultrasonic beam are being investigated.

Teamwork strengthened my position, as Ibrahim "starred" again,

alerting me to less-widely-known Standards showing ultrasonic

test-block configurations and their suggested applications.

Which validated what was first-principles obvious. Some of the